“When Insurers Exit: Climate Losses, Fragile Insurers, and Mortgage Markets” By Ishita Sen, Parinitha Sastry, and Ana-Maria Tenekedjieva

Our focus paper this month links the cost of extreme weather events to home insurer flight, insurer insolvency, and mortgage delinquencies. As devastated homeowners and renters struggle to rebuild after unprecedented flooding in the Appalachian hills, increasingly frequent hurricanes in Florida, and deadly wildfires in Los Angeles, insurance providers are canceling coverage, exiting particular states completely, and making premiums skyrocket. The headlines are impossible to ignore. This paper adds helpful historical context to the mix, outlining how qualitative changes to insurance markets in so-called high-risk states have been underway since the early 2000s and have spilled over into mortgage markets and driven mortgage delinquencies.

In “When Insurers Exit: Climate Losses, Fragile Insurers, and Mortgage Markets,” authors Ishita Sen, Parinitha Sastry, and Ana-Maria Tenekedjieva deconstruct specifically how this chain of events has played out in Florida.

Key Findings:

Increased climate disasters in Florida—a highly climate-vulnerable state—have led traditional insurers to cancel policies and refuse to underwrite new ones. New, smaller, financially fragile insurance providers that are less diversified and demonstrate higher insolvency rates are filling this gap.

Emerging ratings agencies, like Demotech, are offering inflated financial strength ratings to fragile insurance firms, qualifying them for securitization by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, two government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs).

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac accept the ratings given and impose no additional fees to lenders who rely on these fragile insurers. This means that private lenders are not charged extra to offload loans attached to risky insurance policies.

In Florida counties where fragile insurers dominate the market, homeowners are 4.6 times more likely to experience serious mortgage delinquencies following a climate disaster.

Why It Matters:

The authors’ results indicate that “further increases in insurer fragility could cause a surge in serious mortgage delinquencies.” When those delinquencies move onto GSE balance sheets, taxpayers are potentially on the hook in the event of a bailout.

Underpricing of climate risk in insurance and mortgage contracts has led more people to move to high–climate risk geographies in part because the ability of lenders to sell mortgages to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, even when the insurance is fragile, masks the cost of potential damage.

Demotech-rated insurers are not only local to Florida: They hold over one-third of market share in the riskiest states in the US, suggesting that comparable dynamics could be playing out beyond Florida in other states experiencing high costs of climate disasters.

Insurance commissioners have eased the frequency and stringency of their oversight as they focus on the need to ensure that policies are available.

Is This Fed Business?

The dynamics playing out in the home insurance market in particular states are troublingly similar to the rising action leading to the 2008 housing market crash—notably, (i) lagged ratings by rating agencies in pricing financial risks and (ii) the threats to undercapitalization of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac due to home mortgage portfolios with unpriced risks.

Insurance and housing markets implicate macroeconomic performance. Just as fragile insurer insolvency will have implications on mortgage delinquency, insurer flight and inaccessibility of coverage can drive housing shortages, disrupt wealth-building through home ownership, and drive cost of living inflation. To be credible, Federal Reserve models of macroeconomic performance should embed these relationships, particularly as they are revealed in extreme weather events.

To the extent that the Federal Reserve monitors inflation using the Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) indicator, it should consider the effect of the price of property insurance on household inflation. Especially as the existing insurer infrastructure suffers extreme strain, understanding insurance market dynamics is necessary to interpret aggregate inflation measures.

To the extent the Federal Reserve monitors financial stability, it should be watching the implications of mounting regional crises—especially as climate disasters increase in frequency and severity and shift beyond their historical geographies, becoming less localized and less subject to self-executing market correction. If the Federal Reserve believes it can correct after-the-fact, it is worth noting that reactive approaches to crises are more costly than prophylactic, before-the-fact approaches.

There is precedent for the Federal Reserve to investigate catalysts for systemic risk that stem from nonfinancial markets. For example, upon request from ranking members of the Senate Banking Committee, the staff of former Federal Reserve Board Chairman Ben Bernanke prepared a white paper detailing the vulnerabilities of the housing market following the 2008 crash and provided policy guidance. The white paper was published in 2012, a few years too late to contribute to prophylactic interventions, but still demonstrates the scope Federal Reserve leadership can and should cover. Mortgage delinquencies stemming from climate-driven insurance market failures are well within that scope.

Last week, Powell mused in his semiannual testimony to Congress that we might see a world in which people cannot acquire mortgages due to uninsurability. While we acknowledge his acknowledgment, musing is not sufficient. The Federal Reserve should be deeply involved in analyzing the implications of uninsurability to financial markets, safety and soundness, model validity, and economic projections.

A Closer Look at the Research

The first section of the paper documents trends in the insurance market in Florida from 1996 to 2018. The authors show that as traditional insurers—those rated by traditional ratings agencies like S&P or AM Best—exited the market due to mounting climate risk in Florida, new insurers entered to fill the gap. The authors describe these new entrants as “financially fragile insurers,” characterized by high rates of insolvency, underwriting activities concentrated in riskier areas, less diversification across geographies and across levels of risk, lower quality reinsurers (insurance for insurance companies), and ratings by nontraditional ratings agencies. The market share of financially fragile insurers has grown significantly, and they now dominate the market for insurance in Florida.

The rating agency for these insurers is an entity called Demotech, which was founded in 1985 to rate regional and specialty insurance companies. Only in 2022 was Demotech accredited by the Securities and Exchange Commission as a nationally recognized statistical rating organization (NRSRO). Relevant charts from the paper are duplicated here:

Demotech is far less stringent in its assessment of financial strength than conventional ratings agencies, and regularly awards high ratings to fragile firms. The graph above shows that since the early 2000s, Demotech-rated insurers have overtaken traditional insurers in terms of total premiums written.

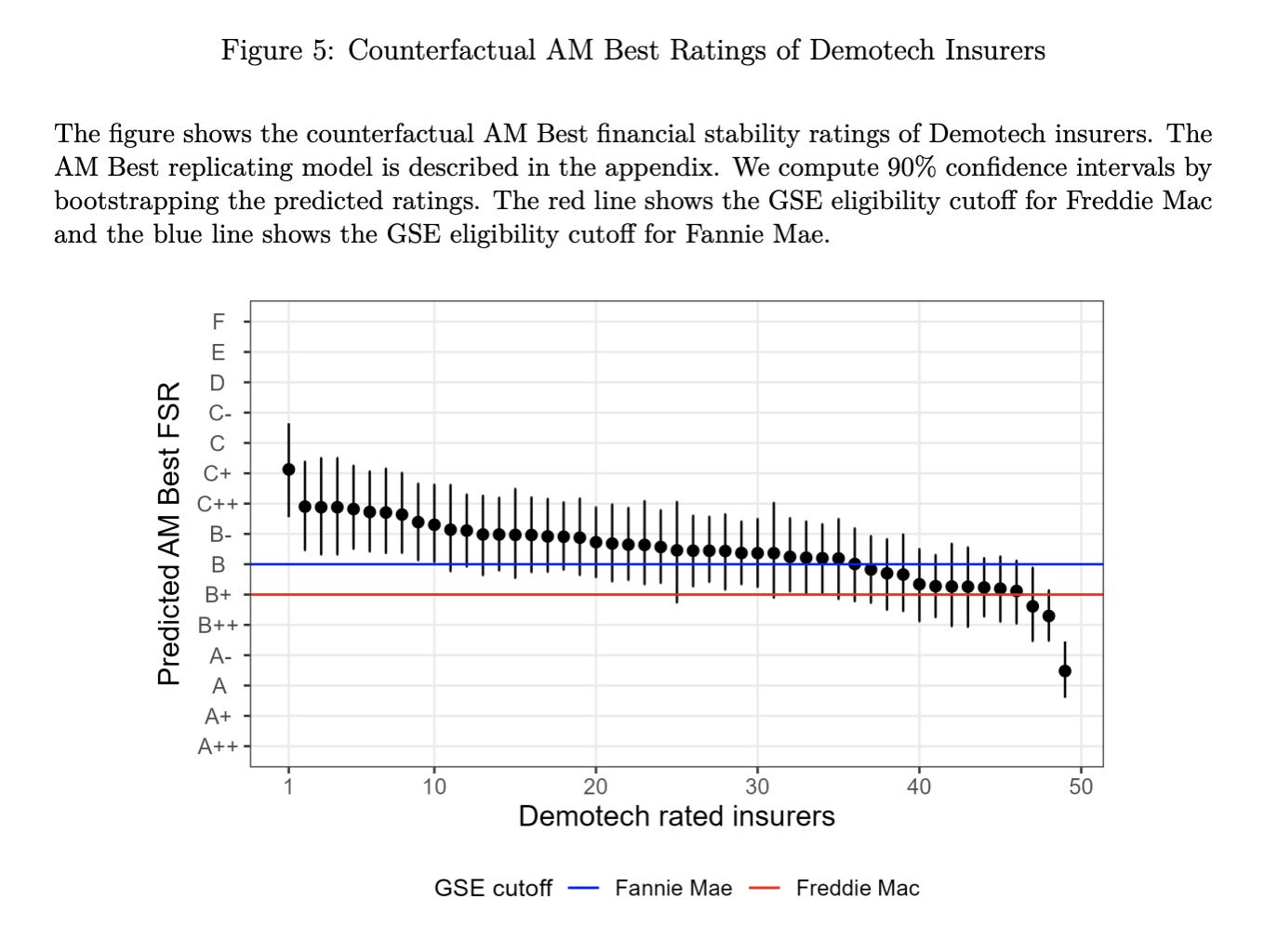

Importantly, Demotech insurers are awarded ratings high enough to be eligible for securitization by GSEs—in this case, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac—without incurring increased fees charged by the GSEs for their vulnerability. The authors find that if these fragile insurers were assessed by S&P or AM Best, they would not achieve the level necessary to qualify—and the “vast majority would be rated as ‘junk.’” As a result, significant insurance insolvency risk is passed on to GSEs that have not levied additional fees or adjusted their eligibility requirements to account for the growing prevalence of fragile insurers and lax ratings.

An important driver in the growth of the market share of fragile insurers, perhaps ironically, is Florida’s public insurer of last resort: Citizens Property Insurance Corporation. This state-backed nonprofit insurer is designed to provide insurance for those who cannot find coverage in the private market, and ideally to mitigate the vacuum that large insurance provider flight leaves behind. But after several bad hurricane seasons in the 90s, Citizens had expanded significantly, and began its “depopulation” efforts in the 2000s, offloading policies to new entrant private insurers by matching Citizen policyholders with private alternatives. Financially fragile Demotech-rated firms are overwhelmingly absorbing these policies.

Finally, the authors use the experience of Hurricane Irma in 2017 to estimate the impact of fragile insurers on mortgage delinquencies. First, using Florida data covering 67 counties, the authors test the effect of the storm itself on serious mortgage delinquency and find that counties that received a Presidential Disaster Declaration (indicating direct exposure to the storm) experienced nearly a threefold increase in serious delinquency rate, jumping from 1.2 percent pre-storm to 3.5 percent months after. These results are significant, but also intuitive: Geographies that suffered the most damages are likely to bear a greater financial impact.

Next, the authors test the role that fragile insurer insolvency plays in exacerbating post-storm delinquency. Because Hurricane Irma affected households insured by Demotech insurers as well as households insured by traditional insurance providers, the authors were able to isolate and distinguish the role that insurer fragility played at the county level. To measure counties’ level of exposure to insolvent insurers, they calculated the share of total premiums, in 2016, of insurers that later became insolvent following Hurricane Irma. The authors estimate that counties in the 75th percentile of exposure to insolvent insurers experienced a 4.6 times higher increase in mortgage delinquency over the pre-hurricane baseline than counties in the 25th percentile of exposure.

We find that these results convincingly demonstrate the impact of climate disasters on household financial stability and the compounding instability that comes from overreliance on risky insurance providers. As we and several others have said, the Fed should take climate-driven insurance breakdown seriously.

To cite this paper:

Sastry, Pari, Ishita Sen, and Ana-Maria Tenekedjieva. "When Insurers Exit: Climate Losses, Fragile Insurers, and Mortgage Markets." Harvard Business School Working Paper, No. 24-051, February 2024. (SSRN Working Paper Series, No. 4674279, December 2023.)