Issue 8: Temperature + Precipitation Rise → Economic Damages → Inequality

Welcome back to Fed Lit, our monthly newsletter profiling essential climate literature for Federal Reserve staff, leadership, and all other interested parties.

“Estimating Economic Damage from Climate Change in the United States” by Solomon Hsiang, Robert Kopp, Amir Jina, James Rising, Michael Delgado, Shashank Mohan, D. J. Rasmussen, Robert Muir-Wood, Paul Wilson, Michael Oppenheimer, Kate Larsen, and Trevor Houser

In past issues of Fed Lit, we’ve discussed studies showing the pathways through which climate events can affect economic damages. Here’s another study with a different pathway—this one being the pathway of inequality. In her 2013 speech at the 22nd Annual Hyman P. Minsky Conference on the State of the US and World Economies, Sarah—then a member of the Board of Governors at the Federal Reserve—made a strong case for examining the role that wealth and income inequality play in undermining economic strength and stability. She argued that ongoing inequality leading up to the 2008 recession could very well have contributed to the magnitude of suffering for low- and middle-income households, and further prolonged their recovery and the recovery of the US economy.

Addressing inequality is neither explicitly nor traditionally included in the Fed’s mandate; indeed targeting the myriad causes of inequality are not the exclusive role of the Fed. But Sarah argues, “If inequality played a role in the financial crisis, if it contributed to the severity of the recession, and if its effects create a lingering economic headwind today, then perhaps our thinking, and our macroeconomic models, should be adjusted.”

With this perspective in mind, we profile a paper this month that estimates how higher average temperatures lead to unequal economic outcomes even in developed countries—in this case, the United States—and exacerbate income inequality at the county level.

Key Findings

At 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming, the authors estimate a decrease in US GDP growth in the range of 0.6–1.7 percent. At 4 degrees Celsius of warming, the decrease in national GDP growth is in the range of 1.5–5.6 percent. In an even more extreme scenario of 8 degrees Celsius of warming, national GDP growth could drop annually in the range of 6.4–15.7 percent.

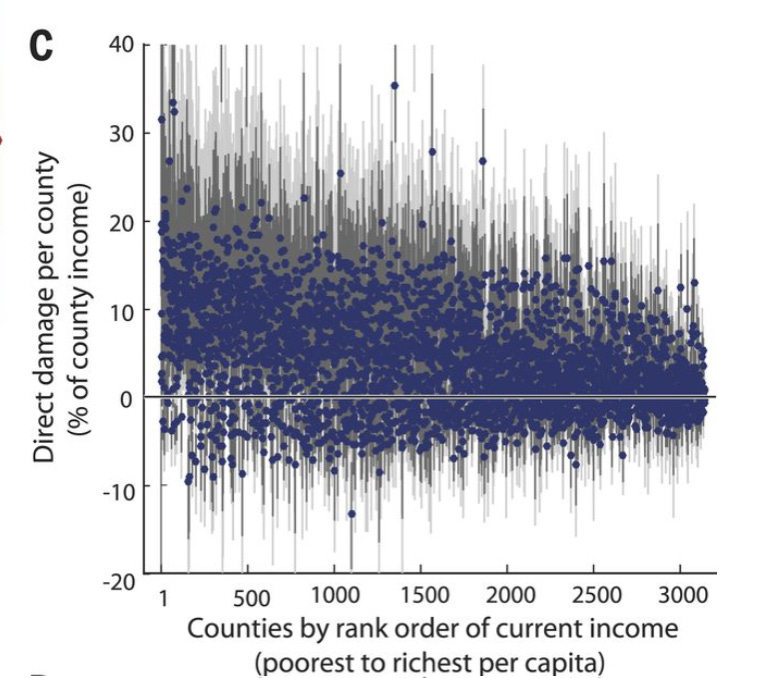

At the county level, the authors find that richer counties experience lower levels of economic damage than poorer counties.

In the richest third of counties, average expected damages range from 1.2 to 6.8 percent of county income.

In the poorest third of counties, average expected damages range from 2.0 to 19.6 percent of county income.

Climate change has the potential to redistribute income from high-risk counties to low-risk counties. This amounts to net transfer of value from Southern, Central, and Midwestern counties that experience the largest income losses to the Pacific Northwest, Great Lakes, and New England, where negative income impacts are smaller and in some cases even positive.

Why It Matters

The economic consequences of higher average temperatures will not be evenly distributed among populations even within a single, developed country like the United States. Pre-existing income inequality can be expected to deepen as a result of persistent warming.

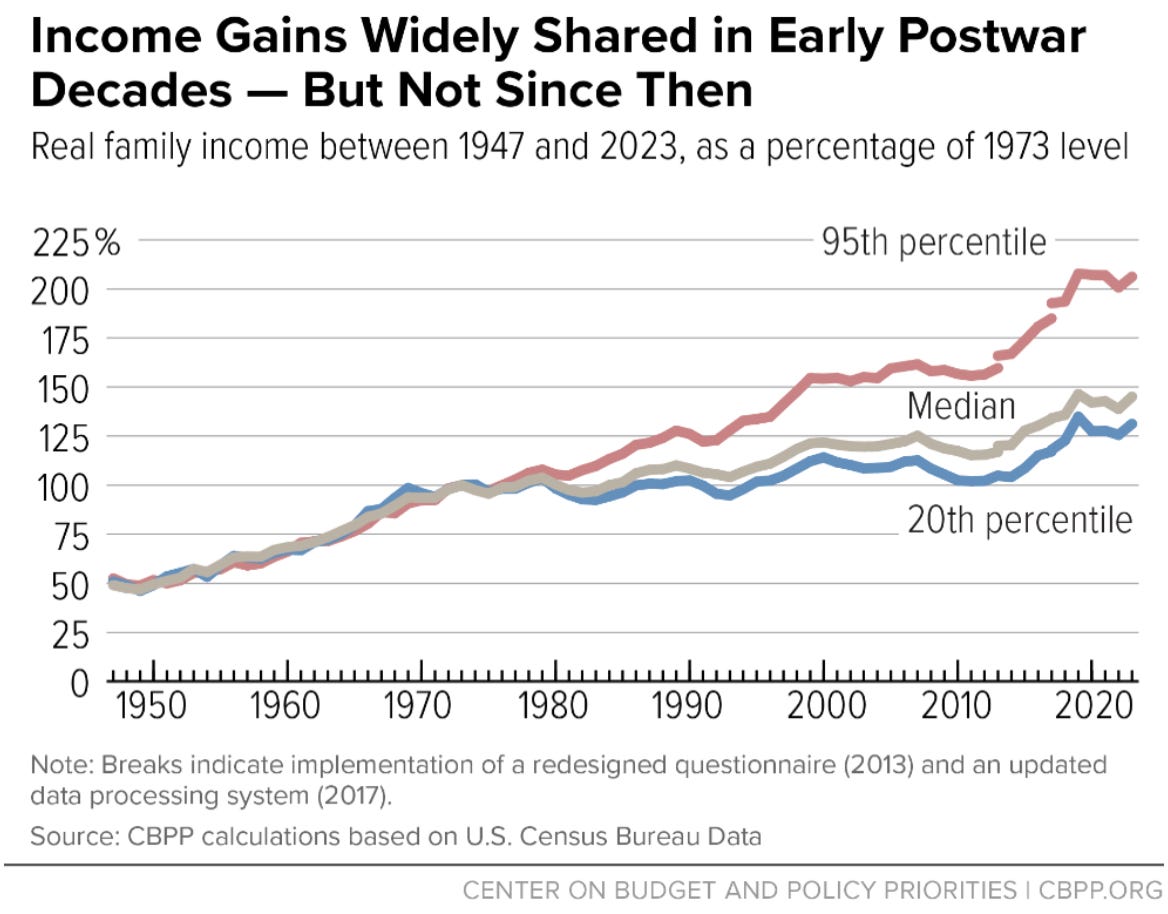

Inequality is already exacting economic and political costs in the United States. It has been growing since the 1970s and intensifying in recent decades, primarily due to shifts in tax policy, weakened unions, and increased financialization. As average temperatures increase, the results of this study suggest that in addition to these factors, we will also need to anticipate climate-driven inequality.

Is This Fed Business?

As Sarah said in 2013, preexisting inequality prolonged the recession in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. The Federal Reserve should quantify inequality to better anticipate the contours of economic growth and loss. This quantification should inform appropriate monetary policy settings, be incorporated in appropriate FRB-US modeling efforts that form the basis of policymaking projections, and be used to better formulate conditions on the uses of the Fed’s emergency lending authorities.

Prior issues of Fed Lit have explored the recent precarity of home insurance providers in the face of mounting climate risk. This paper, while not on the topic of weakening insurance markets, indicates that unequal economic damages arise from both geographic exposure to climate damage as well as populations’ differentiated ability to withstand the financial shock of climate damage. Climate-induced income and wealth inequalities could make the loss of insurance a more likely trigger for an economic downturn that takes longer to reverse.

A Closer Look at the Research

The authors of this paper have set out to create an improved “damage function.” This damage function would convert the various adverse outcomes of climate change into monetary terms, which would then be used in integrated assessment models to conduct cost-benefit analysis for climate mitigation policies.

We believe there are several reasons to be skeptical of this analytical approach, and we’ve criticized the use of integrated assessment models for the variability of their outputs, which depend on the myriad assumptions that go into estimating the monetary value of nonmonetary damages—for example, human mortality. We also question the cost-benefit approach to climate mitigation policy because of the challenges inherent in accurately forecasting the damages that will result from unmitigated climate change. In practice, each estimate must be revised to reflect greater and greater future suffering. It is for these reasons that we believe that climate mitigation must happen proactively; we should codify emissions reduction targets and spend the money necessary to meet them.1

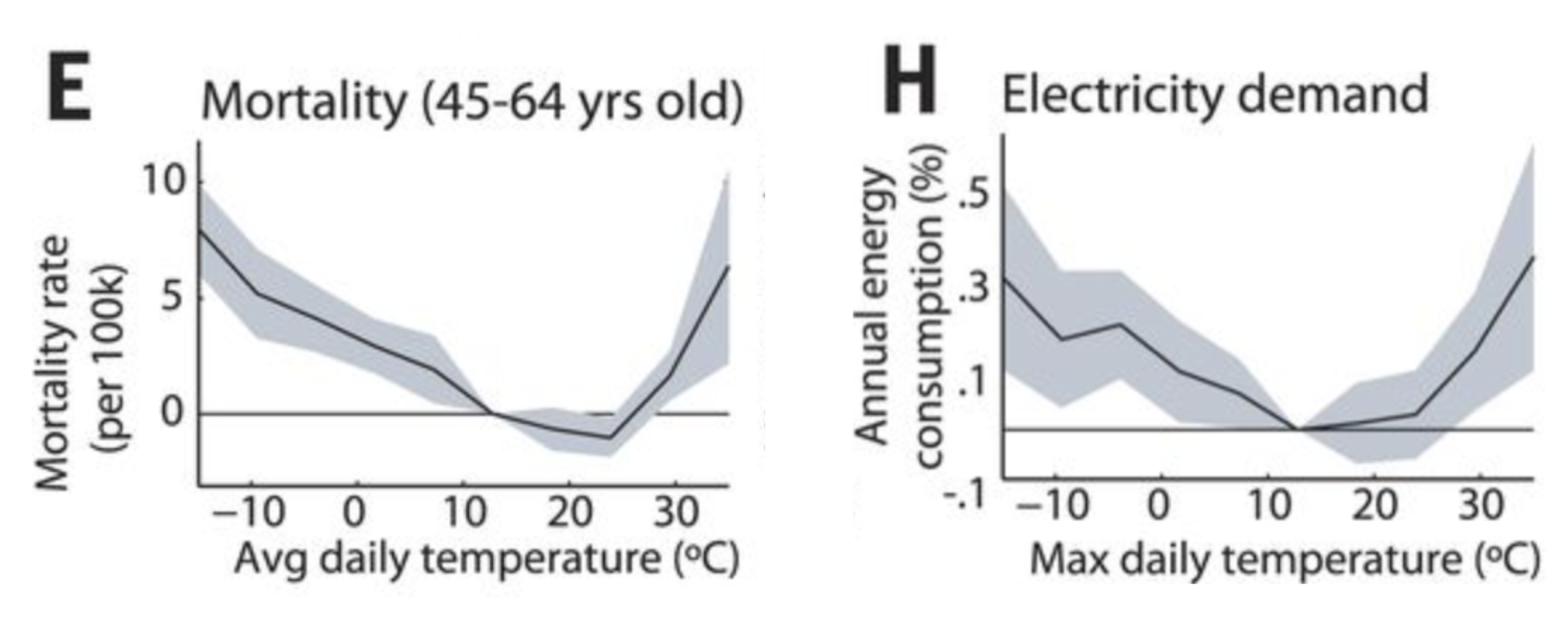

Despite that skepticism, we find this paper promising for its county-specific level of analysis and what it indicates about the unequal distribution of damages that higher average temperatures and precipitation are likely to impose in the US. The authors created county-level projections of temperature and precipitation and tested their impact on various damage categories including agricultural yields, mortality, energy expenditure, low- and high-risk labor supply, coastal damage, property crime, and violent crime. Some categories have a nonlinear relationship with temperature rise and economic damages. For example, the impacts from temperature on energy expenditure and mortality both depend on the starting average temperature of the region. For colder climates, an increase in average temperature can improve mortality and cut energy expenditure, but create the opposite effect in hotter climates.

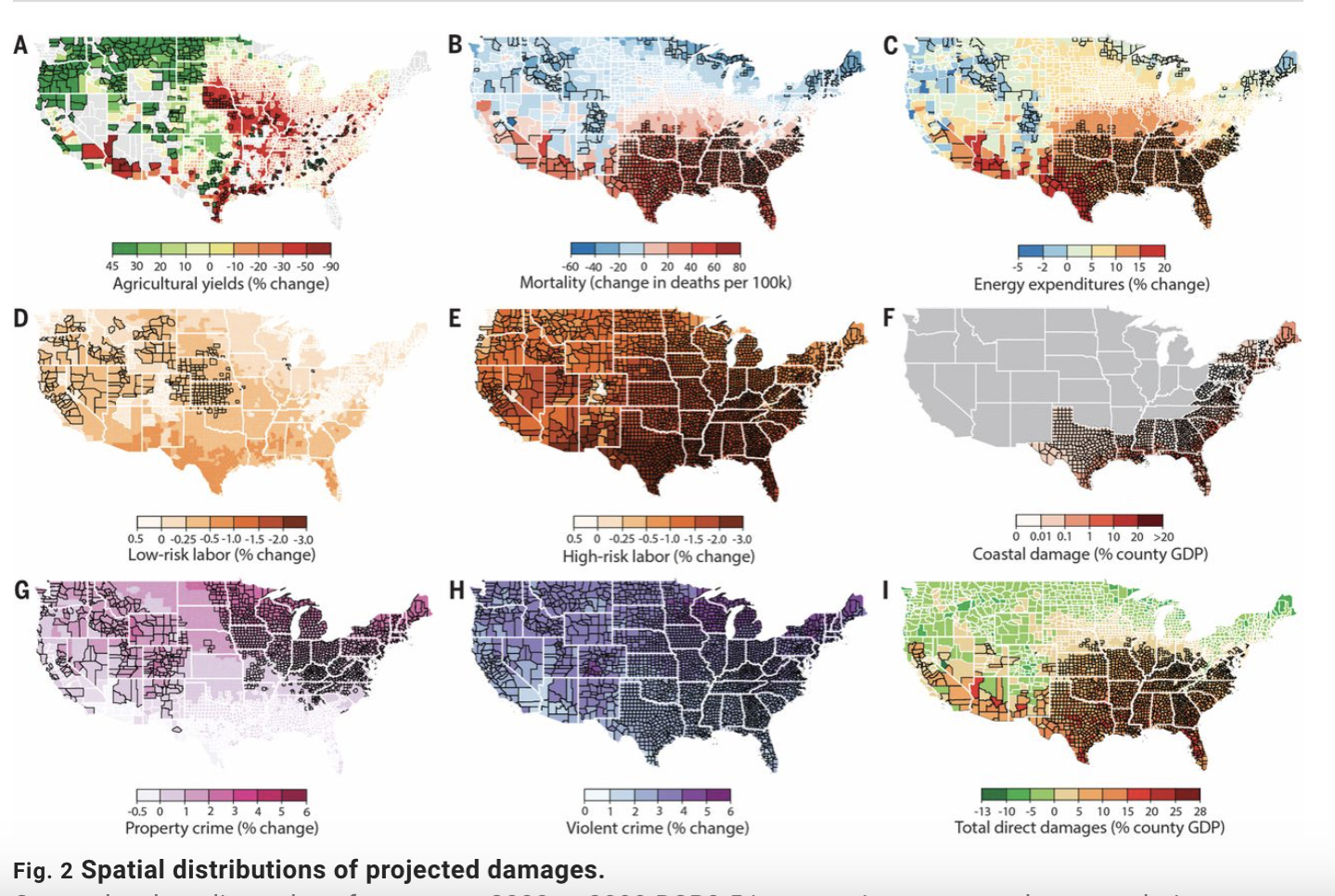

The authors then aggregated these factors to demonstrate the total projected damages by county. The series of maps below shows the projected impacts in a RCP 8.5 scenario by the year 2100, which reflects little to no climate action and a high-emission pathway that leads to 4–5 degrees Celsius of global warming. In map “I,” the regional discrepancy in total damage is stark, with counties in the Southeast, Midwest, and Southwest facing losses of up to 20 percent of gross county product (GCP). On the other hand, some Northern counties are projected to experience economic gains, represented as negative damages, in the context of increases in temperature.

For economic damages in the context of agricultural yields and mortality, it’s clear that increases in average temperatures in cold Northern states can lead to enhanced agricultural yield while increases in average temperatures in hot Southern states can lead to increased mortality. This perhaps-intuitive observation, that higher average temperatures will create new “winners and losers,” benefits from analysis that attempts to quantify these impacts and their purported time path. These maps demonstrate how income and wealth is likely to be redistributed toward regions that are shielded from the impacts of higher average temperatures. The shielding effect could come from the fact that the county benefits from higher temperatures in certain dimensions, or from the fact that the county has invested in enhanced resilience and adaptation that make the impacts less detrimental.

The authors also draw conclusions about how preexisting county income levels correspond with projected income losses. They find that the poorest counties face the largest possible income losses; “[m]edian damages are systematically larger in low-income counties, increasing by 0.93% of county income on average for each reduction in current income decile.” This finding suggests that for low-income counties, recovering from climate damage in time to bear the next disaster may be more costly.

These conclusions are relevant to Sarah’s critique of the macroeconomics profession’s propensity to abstract away from meaningful analysis of inequality. For the Federal Reserve, inequality is neither a formalized indicator of financial instability nor a risk to the macroeconomy. It is not taken into account in the development of macroeconomic models or in the development of the Fed’s use of its emergency lending authority. And yet, as the central bank mandated by Congress to maximize employment in the context of price stability, and to heed risks to the economy reflected in the long-term interest rates, the Fed has a responsibility to study how inequality may jeopardize achievement of these outcomes. Evidence from the 2008 crisis shows that when inequality is preexisting, economic damages are greater and the recovery from recession is prolonged.

In a best-case scenario, the Fed should incorporate the manifestations of growing inequality into its monetary policy decisions, its modeling, and in its emergency responses. The effects of higher average temperatures and precipitation contribute to unequal economic outcomes among regions, in some cases widening preexisting income gaps between parts of the United States. These disparate outcomes can be avoided to some extent by targeting mitigation and adaptation policy tools to affected communities, but it remains the Fed’s role to monitor and anticipate their macroeconomic impacts.

To cite this paper:

Hsiang, Solomon, Robert Kopp, Amir Jina, James Rising, Michael Delgado, Shashank Mohan, D. J. Rasmussen, Robert Muir-Wood, Paul Wilson, Michael Oppenheimer, Kate Larsen, and Trevor Houser. 2017. “Estimating Economic Damage from Climate Change in the United States.” Science 356, no. 6345: 1362–69. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aal4369.

This is the argument that Nicolas Stern and Joseph Stiglitz articulated in 2022 as they proposed an alternative, Marginal Abatement Cost approach to climate policy.